By Sadiq Ahmed

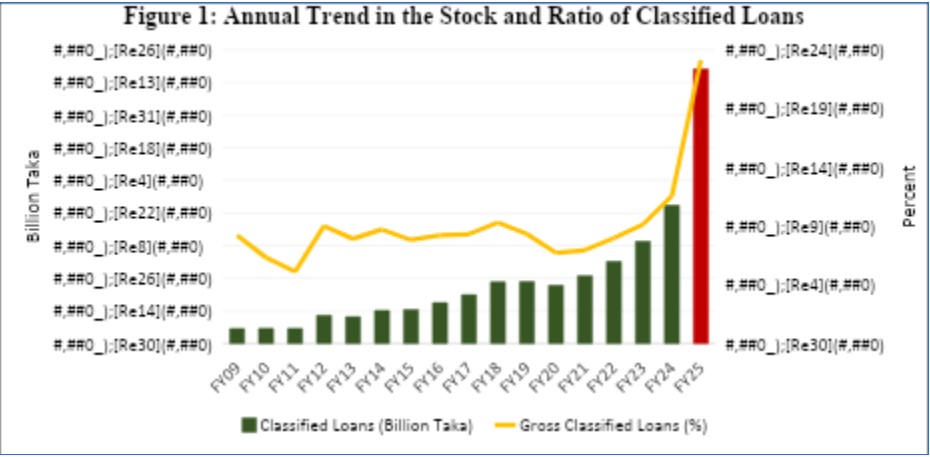

I have been writing about the danger of non-performing loans (NPLs) and the related threat to the stability of the banking sector since 2012. Some 13 years later the problem has escalated astronomically with little signs of reversal (Figure 1). The problem was somewhat muted between FY2012-FY2020 but has gotten out of hand since then. The total value of NPL surged from a low of taka 227 billion in FY2012 to a peak of Taka 4203 billion in FY2025. In terms of share of the total loan portfolio, gross NPLs surged from 6% in FY2011 to 24% in FY2025.

The underlying factors for this rapid deterioration in the quality of the banking portfolio are well known. Basically this is the outcome of poor banking sector governance that is manifested in corruption in bank management, poor lending and loan recovery practices, especially in public banks, large scale thefts often aided by political intervention, ineffective banking sector supervision, and dual banking oversight arrangement under which the public banks are managed by the government while private banks are supervised by the Bangladesh Bank (BB).

With the induction of the Interim Government, it was expected that there would be a sea change in the management, regulation and supervision of the banking sector that will usher in visible positive outcomes in banking sector’s performance.

Indeed, starting in mid-August 2024, some swift actions were taken by the BB to restore the financial health of the 14 weakest performing private banks. These included wholesale board and management changes, injection of new liquidity, and tighter supervision. To improve transparency, asset classification norms were modified to be compliant with Basel 3 norms. Banks were instructed to pursue vigorously the recovery of non-performing loans. A new Bank Resolution Ordinance was adopted in May 2025 that allows BB to take swift actions against any financial institution to protect stability of the banking sector. Several task forces were established to address comprehensively the ills of the banking sector. These include a task force to strengthen the independence of the Bangladesh Bank, a task force to develop bank-specific resolution strategy for handling the problem banks, and a task force to pursue asset recovery options at both home and abroad.

Many of the banking problems are longer- term in nature and solution will take time. Yet, some visible signs of progress have emerged. Most prominently, the bleeding of the banks through outright thefts has stopped. The liquidity situation of several problem banks has improved enabling them to service the deposits of their customers, thereby preventing a threat to the rundown of deposits. New lending decisions are now more professionally managed. The supervision oversight of BB has been strengthened. The progress with asset recovery, however, has been very limited.

What then explains the near doubling of NPLs between FY2024 and FY2025? BB argues that this basically reflects the application of internationally accepted asset classification norms. Previously, the true value of NPLs was hidden through manipulation of the accounting norms and now we have a correct picture of the problem at hand.

While there is no doubt that the true picture of NPLs was hidden previously though accounting gimmicks, it is nevertheless important to do a holistic diagnostics of the NPL problem and changes over the past 10 months. The economy has been going downhill, with GDP growth sliding to 4% or less in FY2025. Businesses have been complaining regularly about cost escalation and weakening of profitability, especially in the manufacturing sector. It is hard to imagine that these factors had no impact on the banking portfolio and the near doubling of NPL is all explained by a change in accounting norms.

A comprehensive resolution of the NPL problem will require two types of interventions: policies that address the flow of new NPLs, and policies that address the outstanding stock based on adoption of Basel 3 loan classification norms for all banks including public banks.

Regarding new NPL flows, first and foremost the actions already taken by BB to stop the bleeding in the problem private banks must be extended to the public banks. The system of dual banking supervision where public banks are supervised by the Banking Division of the Ministry of Finance, must be stopped. All banks, public or private, must be regulated and supervised by BB with full application of Basel 3 norms.

Secondly, to the extent the surge in NPL reflects the underlying economic downturn, swift policy actions are needed to reverse these trends with the implementation of comprehensive reforms in fiscal policy, trade policy, investment climate including establishing the rule of law, improvements in trade logistic and energy supply, acceleration of ITC adoption, and investment in critical skills. The government must understand that not all banking problems are necessarily due to theft and corruption. A significant part may be related to the downturn in the economy and has to be addressed accordingly.

Regarding the stock of NPL, the steps taken by BB are in the right direction, but they have to be substantially strengthened, and implementation must be stepped up. Lessons of good practice experience with resolving banking crisis in developing countries suggest the following comprehensive approach: (1) Actions to restore the financial solvency of the distressed banks; (2) Actions to ensure the profitability of the rescued banks; (3) Actions to close down banks that are inherently unprofitable; and (4) Actions to strengthen built-in mechanisms for preventing future banking crisis.

Restoring the financial solvency of distressed banks is relatively easy when the number of problem banks is limited, when recovery prospects for outstanding loans are good, and when there is adequate fiscal space. On all three counts, Bangladesh seems to be in a very difficult situation. BB will nevertheless need to do a full workout of the amount of new financing needed to restore the solvency of the banks that are indeed rescuable and who can be put back in the market on a profitable basis. Once this amount is known, a financing strategy will need to be developed. This, arguably, will pose the biggest challenge to the banking reforms.

The financing strategy will be some combination of additional financing from the Treasury, additional funding from BB, new financing from current owners, and money raised from the capital market by new shareholders. Given the dire fiscal situation and the inflationary risk from BB financing, much of the new financing will have to come from current and future owners. The government may also seek financial support from multilateral development financing institutions like the World Bank and the ADB to help with this banking resolution. Where public financing is involved, it is essential that new capital is injected only into potentially viable banks that can be restored with adequate operational reforms to earn profits from future operations. Furthermore, steps have to be taken to ensure that the Treasury/BB has first claim on profits of the restructured banks to fully recover injected funds.

International experience shows that ensuring profitability of rescued banks is easier said than done. This requires comprehensive banking reforms including sharp improvements in bank management, quality staffing and IT systems, strengthening financial accounting and auditing standards to international norms, strong internal mechanisms for loan supervision and recovery, strong internal controls and risk assessment, and sound outcome based BB supervision.

Some banks are simply non-viable and suffer from inherent governance problems. These typically belong to the public sector. Even though the lending share of public banks has fallen to 25% of total loans, these banks present a huge fiscal risk. Frequent injections of capital from the Treasury notwithstanding, the risk weighted capital of these banks are hugely negative, gross NPL has reached 46%, loan loss provisioning is highly inadequate, and aggregate profitability is negative. These banks are simply non-viable under state ownership. The government will have to face the problem squarely once and for all and bite the bullet.

Policy options include: (a) Privatization of all except the Sonali Bank that will only pursue Treasury functions; (b) Full corporatization and stock market divestment with management control to private shareholders; and (c) Converting the 4 large public banks into narrow bank that allows deposit holding and investment in T-bills but excludes lending, while closing down the two small banks (Basic Bank and the Bangladesh Development Bank). Some private problem banks are also candidates for closure unless owners are willing to invest new capital to restore financial solvency and readiness to face the market with full compliance with Basel 3 prudential norms.

Finally, there is an urgent need to strengthen the built-in banking crisis prevention mechanisms. The most important policy reform here is the need to sharply enhance the deposit insurance scheme. The US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is a good example of how a strong deposit insurance scheme can prevent large scale banking crisis. A second built-in mechanism is to increase the share of equity by increasing the tier 1 capital requirements beyond Basel 3 minimum standards to provide an incentive to bank owners against undue risks. A third reform is the strict implementation of Basel 3 supervision norms for all banks with no exceptions. A fourth crisis prevention action would be to establish a system of bank risk ratings based on independent credit agencies. This information should be publicly available.

Sadiq Ahmed is Vice Chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. He can be reached at sadiqahmed1952@gmail.com.